So you got yourself an old camera, old like from the mechanical camera age, not old like from the battery-powered point-and-shoot era. It’s made of metal, not plastic and if the wrap’s intact it looks like leather ‘cause it is. You probably have a lever that cocks the shutter and something that orbits the lens to change the aperture. More than likely you’ll find the camera isn’t operating at full capacity. I put such cameras into one of three groups (always three).

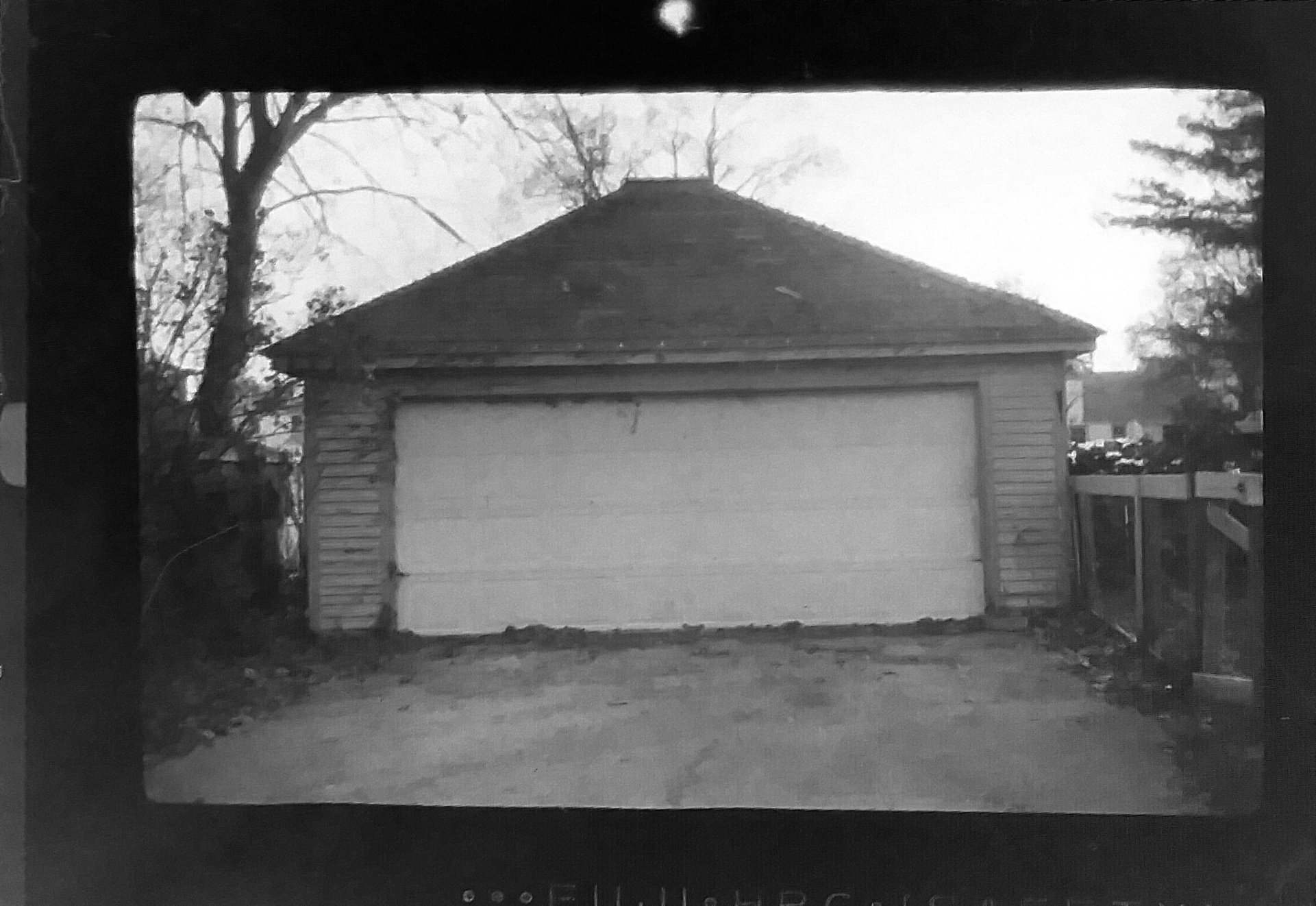

Group One: it basically works. You can focus, set the aperture, cock the fire the shutter, and wind the film on for the next shoot. If you got low standards and can put up with some unpredictable behavior you could go out and have a great time.

Group Two: something doesn’t work. Maybe the focus is so stiff you just always shoot things from 15 feet out. Could be the shutter fires but is like seriously slow, or doesn’t manage to close unless you take your finger off the release even when it’s on 1/50th instead of B. It might have been a whizz-bang tack sharp beauty, but these days it’s got that Lomography aesthetic in spades.

Group Three: it’s a camera shaped paperweight. Someone sold this as a décor item but you were feeling lucky. It may be haunted by the ghost of George Eastman.

A professional could put in the time with their specialist tools and rarefied skills to get any of the above restored. You, like me, do not have those tools or skills and are not willing to leave the trail of bodies in your wake that it’ll take to try and acquire them. Stripped screws, lost springs, gouged metal, and a box of “parts” is all that’s in the cards for any camera with the misfortune to become an attempted aspirational repair. Good news, we’re not doing that. We don’t need any special tools and even if we fail we’re not ending up with a pile of parts that’ll never be a camera again. So what do you need? Patience and heat.

Camera people talk about getting a camera CLA’d. Cleaned, Lubricated, and Adjusted. The important word there is lubricated. Cameras have metal moving parts. Metal on metal is pretty much always lubricated. As with mechanical watches, mechanical cameras tend to use very thin and light lubricant. Thin and light lubricant tends to get thick and tacky after fifty or more years collecting dust. So let’s open it up and spray on the contact cleaner, right? Oh goodness no, that sounds hard. Let’s watch a movie instead.

We Are Now Camera Technicians

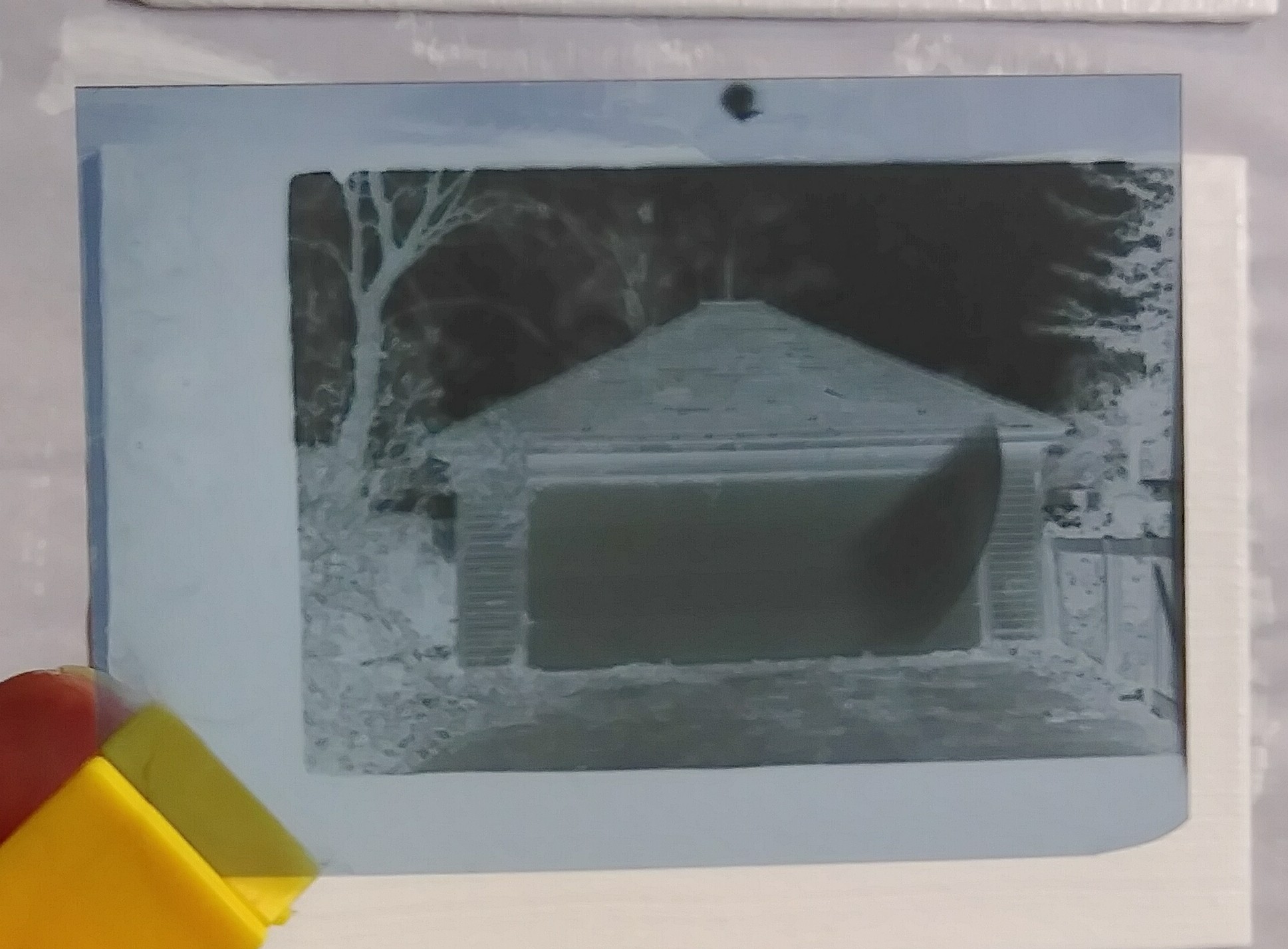

If you have a group one camera, put on a movie, or sit down for a couple episodes of some soon-to-be-canceled Netflix series or ultra-niche podcast. Set a speed, cock the shutter and fire. Then do it again, repeatedly, for every speed, again and again until you run out of media to consume or the will to sit still. Slide the aperture ring back and forth again and again. Focus from one extreme to the other. Get a rhythm going and keep at it. Friction turns to heat that slowly but surely leads to a softening of old lubricant and often it’s enough to clean out the cobwebs so to say and you end up with a reliable camera.

If you have a group two or three camera you’ll be doing the mindless zombie cock-and-fire, twist-and-turn, television session as well. Before you give that a try though, you’ll be baking your camera. If you’re camera’s a folder, open it up. Open the film door too. Now apply heat. If you have a sunny window, push the sleepy cat aside (but apologize with some treats and a dime bag of catnip) and stick your camera in that sunbeam. Hopefully for at least an hour. If it’s overcast, if there’s a draft, or a sunny window is otherwise not an option try putting it in a pot on a radiator. Or preheat your oven at its lowest setting for a good twenty minutes, turn it off, and then pop the camera in for a half hour or more like you’re waiting for bread dough to rise. Like with the radiator though, don’t just sit it on the rack, stick it on a baking sheet or something. With the radiator you want something heavy to help diffuse the heat. In the oven it’s more about keeping it stable on a wire rack.

Remove your camera from whatever heat source you used while it’s still warm. It should be warm, not uncomfortable to hold but more than body temperature. Now go through the motions, adjust the focus and aperture, cock and fire the shutter on all the speeds. You’ll probably find things that were frozen in place before move at least a little now. If you made noticeable improvements, repeat the heating cycle and have another go. If you don’t see any change, well, that’s unfortunate. More heat is not the answer.

Violence. Violence is the answer. Gentle violence. Yes really. If the cameras a folder close it all up and give it a few hammers into your open palm. Don’t do it so hard that you’ll hurt your hand and you can be sure it won’t be so hard as to hurt the camera. Now try that stuck shutter again. If you made a little progress, try a heat cycle again. Then try working all the movements again.

There’s a limit to how much good you can do without taking things apart or spending the money on a professional. If something is genuinely mechanically busted you won’t fix it with a touch of heat, but you won’t turn a mostly working camera into a pile of unusable parts either. I can tell you though, that first time you start with a seized up shutter and come away with a working camera it’s a great feeling.

Holidays are coming and people who have them will make the way back to their ancestral homes. Parents and grandparents and great second what-have-yous-once-removed will be in abundance. Ask these people if they have any old cameras. You’re not looking for 35mm point and shoots, not looking for SLRs, or anything that takes a battery. You want “grand-dads first camera” or “the old Kodak”. Something that folds is good but a hulking box camera works too. They’ll give it to you, just ask.

Holidays are coming and people who have them will make the way back to their ancestral homes. Parents and grandparents and great second what-have-yous-once-removed will be in abundance. Ask these people if they have any old cameras. You’re not looking for 35mm point and shoots, not looking for SLRs, or anything that takes a battery. You want “grand-dads first camera” or “the old Kodak”. Something that folds is good but a hulking box camera works too. They’ll give it to you, just ask.